Sorting Out Stroking Sensations

PASADENA, Calif.—The skin is a human being's largest sensory organ, helping to distinguish between a pleasant contact, like a caress, and a negative sensation, like a pinch or a burn. Previous studies have shown that these sensations are carried to the brain by different types of sensory neurons that have nerve endings in the skin. Only a few of those neuron types have been identified, however, and most of those detect painful stimuli. Now biologists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have identified in mice a specific class of skin sensory neurons that reacts to an apparently pleasurable stimulus.

More specifically, the team, led by David J. Anderson, Seymour Benzer Professor of Biology at Caltech, was able to pinpoint individual neurons that were activated by massage-like stroking of the skin. The team's results are outlined in the January 31 issue of the journal Nature.

"We've known a lot about the neurons that detect things that make us hurt or feel pain, but we've known much less about the identity of the neurons that make us feel good when they are stimulated," says Anderson, who is also an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. "Generally it's a lot easier to study things that are painful because animals have evolved to become much more sensitive to things that hurt or are fearful than to things that feel good. Showing a positive influence of something on an animal model is not that easy."

In fact, the researchers had to develop new methods and technologies to get their results. First, Sophia Vrontou, a postdoctoral fellow in Anderson's lab and the lead author of the study, developed a line of genetically modified mice that had tags, or molecular markers, on the neurons that the team wanted to study. Then she placed a molecule in this specific population of neurons that fluoresced, or lit up, when the neurons were activated.

"The next step was to figure out a way of recording those flashes of light in those neurons in an intact mouse while stroking and poking its body," says Anderson. "We took advantage of the fact that these sensory neurons are bipolar in the sense that they send one branch into the skin that detects stimuli, and another branch into the spinal cord to relay the message detected in the skin to the brain."

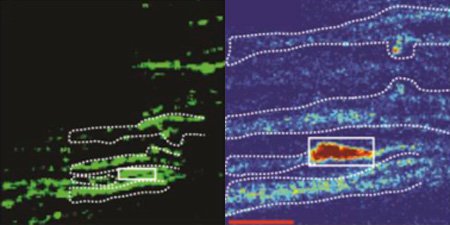

The team obtained the needed data by placing the mouse under a special microscope with very high magnification and recording the level of fluorescent light in the fibers of neurons in the spinal cord as the animal was stroked, poked, tickled, and pinched. Through a painstaking process of applying stimuli to one tiny area of the animal's body at a time, they were able to confirm that certain neurons lit up only when stroked. A different class of neurons, by contrast, was activated by poking or pinching the skin, but not by stroking.

"Massage-like stroking is a stimulus that, if were we to experience it, would feel good to us, but as scientists we can't just assume that because something feels good to us, it has to also feel good to an animal," says Anderson. "So we then had to design an experiment to show that artificially activating just these neurons—without actually stroking the mouse—felt good to the mouse."

The researchers did this by creating a box that contained left, right, and center rooms connected by little doors. The left and right rooms were different enough that a mouse could distinguish them through smell, sight, and touch. In the left room, the mouse received an injection of a drug that selectively activated the neurons shown to detect massage-like stroking. In the room on the right, the mouse received a control injection of saline. After a few sessions in each outer room, the animal was placed in the center, with the doors open to see which room it preferred. It clearly favored the room where the massage-sensitive neurons were activated. According to Anderson, this was the first time anyone has used this type of conditioned place-preference experiment to show that activating a specific population of neurons in the skin can actually make an animal experience a pleasurable or rewarding state—in effect, to "feel good."

The team's findings are significant for several reasons, he says. First, the methods that they developed give scientists who have discovered a new kind of neuron a way to find out what activates that neuron in the skin.

"Since there are probably dozens of different kinds of neurons that innervate the skin, we hope this will advance the field by making it possible to figure out all of the different kinds of neurons that detect various types of stimuli," explains Anderson. The second reason the results are important, he says, "is that now that we know these neurons detect massage-like stimuli, the results raise new sets of questions about which molecules in those neurons help the animal detect stroking but not poking."

The other benefit of their new methods, Anderson says, is that they will allow researchers to, in principle, trace the circuitry from those neurons up into the brain to ask why and how activating these neurons makes the animal feel good, whereas activating other neurons that are literally right next to them in the skin makes the animal feel bad.

"We are now most interested in how these neurons communicate to the brain through circuits," says Anderson. "In other words, what part of the circuit in the brain is responsible for the good feeling that is apparently produced by activating these neurons? It may seem frivolous to be identifying massage neurons in a mouse, but it could be that some good might come out of this down the road."

Allan M. Wong, a senior research fellow in biology at Caltech, and Kristofer K. Rau and Richard Koerber from the University of Pittsburgh were also coauthors on the Nature paper, "Genetic identification of C fibers that detect massage-like stroking of hairy skin in vivo." Funding for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Human Frontiers Science Program, and the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation.

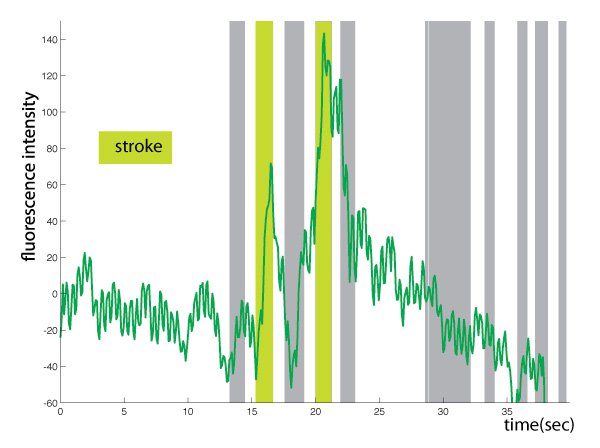

This graph represents a quantitative readout of the increases in fluorescence measured with the microscope as a stroke stimulus was applied to the animal's skin. Vertical yellow bars indicate periods when the stroke stimulus is applied and peaks in fluorescence coincide with the delivery of the stroke stimulus.

Credit: Anderson Lab / Caltech

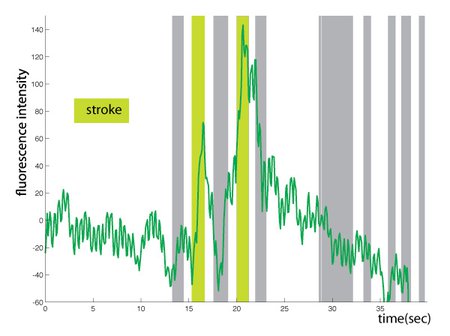

This graph represents a quantitative readout of the increases in fluorescence measured with the microscope as a stroke stimulus was applied to the animal's skin. Vertical yellow bars indicate periods when the stroke stimulus is applied and peaks in fluorescence coincide with the delivery of the stroke stimulus.

Credit: Anderson Lab / Caltech

Left: An image of fluorescent nerve fibers in the spinal cord, viewed through the microscope prior to stimulation. Right: A magnified view showing the increase in fluorescence signal in one specific fiber (boxed area, red color) during stroking with the brush.

Credit: Anderson Lab / Caltech

Left: An image of fluorescent nerve fibers in the spinal cord, viewed through the microscope prior to stimulation. Right: A magnified view showing the increase in fluorescence signal in one specific fiber (boxed area, red color) during stroking with the brush.

Credit: Anderson Lab / Caltech